by Andrew Horton

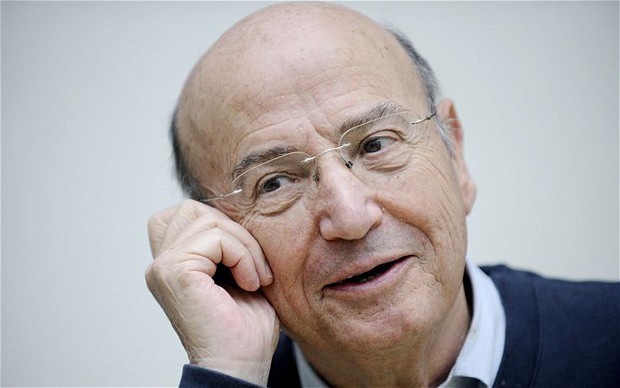

Theo Angelopoulos

Theodoros Angelopoulos, the renowned Greek filmmaker died as he had lived, making movies. In an absurd moment that might have come from one of his films, he was accidentally struck by a motorcyclist on January 24th, while preparing a scene of his latest film, The Other Sea. The horrific death of the man universally referred to as Theo was especially disheartening given the current cultural malaise in Greece, a time when many Greeks are echoing Theo’s query in The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991), “How many borders do we have to cross to reach home?”

I was fortunate to be able to be on the set of The Other Sea just a few weeks before his tragic accident. Theo had asked for my comments on his script. I also spoke with Phoebe Economopoulou, Theo’s wife, and producer of many of his films, and got to meet with his three daughters who have been working on the film. Eleni is shooting a documentary about the making of The Other Sea, Anna has been casting, and Katerina is the production designer.I have been on film sets and film shoots around the world, but I felt a very special spirit from The Other Sea crew. Theo was in top form, anxious to make his new film the crowning glory of the trilogy that began with The Weeping Meadow (2003) and The Dust of Time (2008).

Theo achieved world renown by his distinctive individually crafted cinema that was simultaneously intensely Hellenic and universal. In an early study of his work, I stated what I still feel is the reason his films continue to speak to audiences around the world.1

“His films matter “because they dare to cross a number of borders: between nations, between history and myth, the past and the present, voyaging and stasis, between betrayal and a sense of community, chance and individual fate, realism and surrealism, silence and sound, between what is seen and what is withheld and not seen, and between what is ‘Greek’ and what is not. In short, Theo Angelopoulos can be counted as one of the few filmmakers in cinema’s first hundred years who compel us to redefine what we feel cinema is and can become. But there is more. His films open us to an even larger question that becomes personal to each of us: how do we see the world within ourselves and around us?”

Born in 1935, Theo was raised during the tumult of the German Occupation of World War II and the Greek Civil War (1946-1949). This period included an incident when his father was taken hostage and nearly lost his life. After the war, Theo studied law in Athens and in the late 1950s he moved to Paris to study cinema. Theo returned to Athens in 1964, a year after the murder of Gregory Lambrakis,2 which had set off a political crisis that would led to the military junta of 1967-1974. Before making his own films, Theo worked as a film critic and wrote about the need for Greek filmmakers to go beyond the commercial cinema that had dominated Greek filmmaking since the end of World War II. His first feature, Reconstruction (1970 ), a black-and-white drama set in the Greek countryside, won first prize in the Thessaloniki Film Festival and a FIPRESCI prize at Berlin.

His great masterpiece, The Travelling Players (1974/75), begun during the final years of the Greek junta, provides a coda to his entire body of work. The film views Greek history and culture from the late 1930s to the early 1950s from a decidedly Marxist perspective never before seen in Greek cinema. Theo always insisted on presenting “the other Greece,” which, in his mind, was, in fact, the real Greece, rather than the sunny postcard Greece of tourism. His films often dealt with the effects of war, emigration, and authoritarian society on families and communities far from Athens. In the course of his life, Theo claimed to have visited every village in mainland Greece to find appropriate sites for his films. His stories often involved scenarios set in snowscapes or in the rain. During the making of Eternity and A Day (1998), which had many scenes set in Thessaloniki, when it rained or the sky was gray, Thessalonikians would quip that Theo must be working on his film.

The Travelling Players, although almost four hours long and filled with avant-garde-cinema techniques, was not a hothouse orchid. In the fervent period of postjunta Greece, it broke all previous attendance records for any Greek film. Many Greeks returned more than once to grope with the film’s powerful visual style and the ideological argument. The film won international awards at Berlin (Forum of New Cinema Award), Cannes Film (FIPRESCI prize), Tokyo (the Kinema Junpo Award for best foreign language director) and Britain (the Sutherland Trophy awarded by the British Film Institute). This would set the pattern for the following films, including two awards at Cannes, the Grand Jury Prize for Ulysses’ Gaze (1995), and the Palme d’Or for Eternity and a Day (1998).

Renowned film scholar David Bordwell summed up Theo’s cinematic legacy quite well when he wrote, “That Angelopoulos can receive such renown today suggests that, for many viewers, the postwar tradition has not exhausted itself, that it can endow our world of snack bars, video clips and ethnic wars with an astringent, contemplative beauty. At a moment when European cinema, both popular and elitist seems to be breathing its last, Angelopoulos’ work is particularly important.”3

My friend and Cineaste Consulting Editor, Dan Georgakas, has often observed that Angelopoulos was totally immersed in Hellenic culture. Nearly every film is coded with classical references and the films frequently use Byzantine images and historical personalities to probe the roots of contemporary Greek society. In The Travelling Players, a troupe of actors keeps trying to perform Golfo, a populist play with a Romeo and Juliet romance compromised by the traditions of rural Greece. During the film, the play’s performance is always interrupted, Theo’s sly way of stating that the Greek villages of legend never existed. In all his work, Theo offered a stream of historical, metaphorical, and personal commentary on the ongoing controversy regarding the nature of the Greek national character that applies to all cultures. Theo’s vision indeed resonated with audiences far beyond the borders of Greece, but in terms of Greek cinema, his influence was monumental. Georgakas notes that, as was said in the United States when Ernest Hemingway began to publish, half the directors in Greece tried to imitate him and the other half tried not to.

Theo could be a traditionalist as well as an innovator. He thought films were an art form that needed to be experienced in a theater with a live audience. In that respect, for many years he would not allow his films to be put on DVD formats, as he felt they could not be understood on a small screen and were not meant for individual contemplation. On the other hand, Theo insisted that audiences must be willing to do some work to deal with a serious art form and not passively consume celluloid images as if they were kernels of popcorn. Theo offered what I call his “cinema of contemplation,” with shots that last between two and five minutes and sometimes longer, a sharp contrast to the average Hollywood film with its rapid cuts often lasting only seconds. In one scene in The Travelling Players, a train rider virtually leaves the film by looking directly into the camera and speaking at great length about the Turkish atrocities in Asia Minor. At another point, a man listening to military music and right-wing oratory in 1952 walks down the street to emerge into another square with the same music and oratory, but it’s now 1938. In The Weeping Meadow, a town is slowly engulfed by a rising flood tide. There are no jump cuts, just the slow agony of drowning.

Theo was a self-conscious auteur who created films with a distinctive director’s “gaze.” Nonetheless, he had close and harmonious relations with his cinematographers, musical directors, and other creative coworkers, many of whom worked with him again and again. This cordiality was not limited to his closest collaborators or famous persons. Ellen Athena Catsiakas, a young Greek American who worked on Ulysses’ Gaze in a minor capacity, has commented how supportive he was to someone at the onset of her career. Dan Georgakas notes how Theo was always available for a chat and always remained sensitive to the nuances of various national cultures. At a formal talk Theo was delivering to hundreds at the Thessaloniki Film Festival, he spotted Georgakas standing in one of the aisles and stopped his castigation of the commercial film culture of Hollywood to say that there were also American magazines, like Cineaste, that he greatly respected. And I will never forget that, in 1975, when The Travelling Players was filling cinemas, Theo took time to come to speak with my literature and film class at Deree College in Athens that I was teaching then, an act that marked the beginning of our thirty-seven-year friendship.

The Other Sea was intended to address his signature themes of national and personal identity. The script takes on the contemporary Greek crisis including strikes, illegal immigrants from Afghanistan and the Middle East, a rising suicide rate, historic unemployment, and unprecedented personal violence. Reprising and updating the Golfotheme, a new set of “travelling players” attempts to perform Brecht’s Three Penny Opera. While The Other Sea is now fated to never be finished, or, as the Europeans say, “realized,” we have seventeen completed films.4 Some are more powerful than others to be sure, but all underscore with great intensity and artistic integrity that the nature of our personal and national journeys is far more critical than our projected final destination.

- Andrew Horton, The Films of Theo Angelopoulos: A Cinema of Contemplation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997: revised edition, 1999).

- Chronicled by Costa Gavras in Z (1969) from a novel of the same title written by Vassilis Vassilikos.

- “Modernism, Minimalism, Melancholy: Angelopoulos and Visual Style,” in The Last Modernist: The Films of Theo Angelopoulos, edited by Andrew Horton (NY: Praeger Books, 1997).

- Angelopoulos’s Website is www.theoangelopoulos.gr.

Andrew Horton is a Cineaste Associate and The Jeanne H. Smith Professor of Film and Media Studies at The University of Oklahoma.

Copyright © 2012 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXVII, No. 2