Репортажі Ріа Клайман з подорожі по Східній Україні і Кубані наприкінці літа 1932 р.

22.11.2014

Ріа Клайман: забута очевидиця Голоду 1932-33

Rhea Clyman: A Forgotten Eyewitness to the Famine of 1932-33

“Truth, Does It Matter? Is It Constructive”

[Heading above photo of Rhea Clyman]

The caption to the photo reads: Miss Rhea Clyman, for four years special correspondent of The Evening Telegram in Russia, has returned to Toronto. Driven out of the land of the Soviet because she dared to write about Kem, that grim prison fortress near the Arctic circle, Miss Clyman faced death at the hands of the secret police.

During her four years in Russia, she mastered the language, and it was because she was able to converse freely with the people and gain actual facts about present day conditions that the Red Government decided she was a “dangerous person.” When Miss Clyman faced a high Soviet official in Moscow and demanded the real reason for her explusion, he replied: “Truth―does it matter? Is it constructive?”

In the accompanying article, Miss Clyman begins an uncensored story of the Russia of to-day. Other interesting articles will appear exclusively in The Telegram.

Evening Toronto Telegram, 8 May 1933, p. 1.

Dares Warning of Death / To Discover Grim Secret / Of Russia’s Famine-Land

Woman Takes Unmapped, Hazardous Trail Despite Dissuasive Efforts of Soviet and Embassies

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

What is the truth about Soviet Russia? All the world is asking this.

Bankers and businessmen want to know if the Soviet Government is stable and will endure, and if their credits and exports are guaranteed. Economists talk about State planning, politicians about Soviet foreign relations. But the simple, ordinary people, the men and women who are not interested in Soviet doctrines, and to whom the policy of class-hatreds and dialectical materialism carries no threats, ask only one thing―what is happening to the Russian people? What have they gained by the revolution? How do the 160,000,000 people live now?

It was to answer these questions that I set out on a 5,000 mile journey by automobile through South Russia, the Ukraine, the Don Cossack Republic and the Caucasus. I had lived four years among the Russian proletariat in Moscow. I knew how easily they were swayed by propaganda and faked sabotage trials, I could see how the fire of class-hatred was kept alive for and by them. But those other people, the dark Russian mujik, whose roots were in the soil, the Ukrainian peasant, the best land cultivator in Russia, the Don Cossack fiercely proud and possessive, the coal miner, the oil worker, the moulder and steel roller, how have they fared under fifteen years of Communist rule?

ALONG FAMINE TRAIL

My route followed the great Soviet coal industries, the Grozny and Baku oil and refining plants, the huge electrical development schemes at Dnieper, and the steel and iron mills in the Donetz. The battle for the five year plan was being fought out there. There was no motor road beyond Kharkov, the capital of the Ukraine; I followed the old caravan route and wagon trails left by Ghengis Khan and Tamerlaine.

The Caucasus and the Ukraine were once the granaries of all the Russias. The socialization of agriculture began there. In the Don Cossack regions are the huge Soviet State farms, Gigant and Verblud. The farms that were to pour an unceasing flood of grain on the Soviet export markets.

The last figures published by the Soviet Government stated that all this territory is now 90 per cent collectivized. But when I left Moscow, I knew there was famine raging there. Stalin’s policy had failed, the socialization of agriculture was a failure. Will rumors were going the rounds of Moscow Government circles; a peasant uprising in the Don Cossack regions, grain collections were being made at the point of a gun, and there were whispers about even cannibalism and famine atrocities.

WARNED BEFORE START

The Press Department at the Soviet Foreign Office did everything to dissuade me from going, but I held firm. Short of forbidding it absolutely, there was nothing they could do.

“You’ll be back in Moscow within a week,” Neuman, the night censor, lisped. “There are no roads. You won’t get any gasoline, and there are no hotels on the route you are following. You can’t live without your hot bath and three meals a day. You’ll come running back to Moscow when you feel the first bedbug bite.”

It was the not the bite of bedbugs that sent me back to Moscow; the peasant homes I slept in en route were swarming with them, nor was it the lack of baths or three meals a day. I suffered untold tortures from the black bread, made of corn chaff and straw, I bought in Rostov when the supply ran out. It was the muzzle of a quick sharpshooting revolver levelled threateningly at me on the street in Tiflis that sent me rushing back to Moscow. Four week[s] after starting out I was brought back from Tiflis by two stalwart secret police guards. Yagoda, the Vice-Commissar of the O-Gay-Pay-Oo,[1] had signed the order for my expulsion from Soviet territory―all because I committed the unpardonable error of learning the Russian language and writing the truth about what I heard and saw.

CITY WITHOUT WATER

It had been very hot in Moscow before my tour of exploration started. Forest fires raged everywhere, a train come down from Archangel had been set on fire by a spark blown onto the roof and over 300 lives were lost. In my flat in Moscow, we went days without water. The Moscow pumping system worked badly even in the winter, and in this hot weather it had given out entirely. The eight children in the two rooms next to mine were not house-broke and life became unbearable.

But it had turned cool suddenly with the rain. That awful implacable rain that pours down on all Russia, lashing the dust into submission and wiping the trees bare; that rains that turns a hot summer into a grim mudcoated [sic] autumn. But the sun had come out from her four days’ hiding to light us on our way.

The newly gilded eagle perched on the top of the Uspensky tower seemed to dip his head knowingly as we sped through the Red Square. The grey-clad solders, minding Lenin’s tomb, left their niches in the shadow to come and pat the shining flanks of our flivver “Becky” when the policeman scolded me for not obeying the traffic lights. “A tight squeeze there,” they called to us as we honked our horn and were off again.

The two American girls who were to be my companions for this journey were not very experienced travellers for Russia. They had driven their car half-way through Europe, brought in tons of luggage, but they had never heard of a food shortage or gasoline famine in Russia.

ROAD MAPS FORBIDDEN

My heart sank when I looked at the luggage that was to be packed into the back of the car. Blankets, bedding, tools, extra tires, cooking and washing utensils and books. I contributed five large round loaves of black bread, that looked like flattened pumpkins and were just as hard to fit in, and seven swelling batons of white bread. The girls wanted to sacrifice the bread and bring the books. But I held firm. Books could be read at home. They did not know that a half pound of white bread would pay for a night’s lodgings in the regions we were bound for. They had never been in a country where food was scarce and bread could not be had for money.

But the chief difficulty of this trip was not going to be food, nor gasoline, but maps. For weeks I ran round Moscow searching for road maps. The Soviet Government had forbidden the publication of large scale maps, anyone who possessed one could had up for counter-revolutionary espionage. I had to leave Moscow with a small blueprint showing a black line where the road to Kharkov might be―beyond that there was no highway―and a sheet torn from a Russian’s diary giving a list of names of the towns I would pass en route.

AMBASSADOR TO RESCUE

This might have been helpful but for the passion the Soviets now have for changing the names of towns and villages every few months. Fifty miles out of Moscow, no one ever refers to a place except by its old name. The memory of those countless miles I lost, those aggravating moments when lost in the mass of little narrow wagon roads―I would consult my slip of paper and then try to make a Ukrainian or Georgian understand that I want to go to Leninsk, although he only knew it as Nicholievsk―still brings blushes of shame to my face.

We had to have extra gasoline containers. I knew that there would be long stretches from town to town, and the prospect of getting stuck on the road with an empty gas tank was not cheering. The garages in Moscow had no tins, nor did any of the stores. We only had one tire chain, the girls had lost the other on the road somewhere. I was willing to leave Moscow with only one chain but not without extra fuel containers.

The French Ambassador, M. Dijon, heard of my difficulties and came to the rescue. He loaned me a five gallon tin and then presented me with two bottles of dry champagne and gave me his blessing for success of the journey.

ADVANCE OBITUARY

The night before starting our embassy rang up. They thought that this trip was a foolhardy venture, the roads would be dangerous after the autumn rains. I would get no gasoline. Our Ambassador, Sir Esmond Ovey, had attempted a short trip by motor but he had to turn back when he ran out of fuel. Then Walter Duranty, of the New York Times, added another warning. He came up to say good-bye and told me that he had my obituary, all written―he promised that it was a good one.

But my plans were all made. The automobile stood in readiness. Boxes of tinned food, tea and sugar were stored away inside, the two bottles of champagne stood inviting to be opened, they would cheer the way.

The children were agog with excitement. They race up and down the five flight [sic] of steps preened with importance. It was their “inastranka,” foreigner, who was going on this journey and to them belonged the honor of keeping all others at bay when “Becky” stood bright and shiny at the door. At the stroke of nine the engine roared, a wild cheer went up, and we were off.

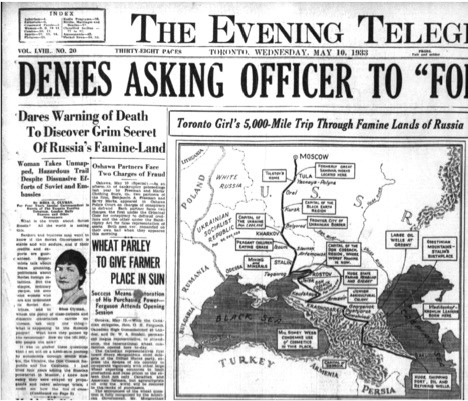

Introduced on the front page alongside of a map tracing the route taken by Rhea Clyman, highlighting key places that she passed through and visited. The header to the map reads, “Toronto Girl’s 5,000-Mile Trip Through Famine Lands of Russia,” while the caption reads:

The dark line marks the route taken by Miss Rhea Clyman on her 5,000-mile motor trip from Moscow to Tiflis and thence by train to Baku. To-day Miss Clyman begins the story of her trip. She travelled, not on paved highways, but along rough unmapped trails, meeting the people of the Soviet Republic whom the ordinary tourist and writer does not see. And she now the story of these people after fifteen years of experimenting with Communism.

Miss Clyman, who lived for four years in Russia and acted as special correspondent of The Evening Telegram, was arrested in Tiflis, and driven out of the country. She had been there too long, she had learned to speak the language and she had heard and seen the truth about the Soviet. She had become a “dangerous person” in Russia.

Start with Miss Clyman to-day and follow her on her trip to Tiflis. Her articles will appear exclusively in The Telegram.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 10 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 2 under the heading “Dares Warning of Death To Discover Grim Secret.”

Girl Writer and Friends / Have to Form “Company” / To Buy Gas From Soviet

System Keeps Peasants Poor ― O-Gay-Pay-Oo Casts Shadow of Ill-Omen Over Journey

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

Gasoline, the staff of our roving life, is as precious as bread in Russia, but even more powerful than bread or gasoline is the O-Gay-Pay-Oo.

On the third day out from Moscow on our 5,000-mile trip to Tiflis we reached Orel and ran out of gasoline. I knew where to head, and in I went. In the office of the secret police I answered less than ten questions and walked out a few moments later with an order on the local gasoline base for twenty gallons. There was a two hours’ wait and a lengthy dispute in the yards of the Naphta Syndicate before we could get our gas. But here, as in everything else, the good-will of the O-Gay-Pay-Oo triumphed over red tape. The two girls and myself had to form ourselves into a limited company, “The Society of the Foreign Correspondent,” before the bill could be made out and the charges adjusted!

“The gasoline base,” the manager explained, “works on credit. No private individual can buy gas, all the bills must be made out against some organization. We the keep the gas here for our tractors, but the gasoline is charged up to the collective farms. We charge all the fuel the tractor units use, and at harvest time the colhozes pay with grain. We don’t sell gas for money, only for grain.”

PEASANTS PAY PLENTY

That partly explained why the members of the collective farms got so little of the grain they produced. The Government owns the gasoline bases, they own the tractors, they control the repair shops, they decide when and how long a tractor should work on the collective farm fields. The Government does not want money from the collective farms, the payments are deferred until the harvest, then the charges are made out and everything is paid for with grain. However, we had managed to get 20 gallons at the ordinary price of 85 copecks (42-1/2 cents) a gallon, and with “Becky” well-filled and all our extra tins securely fastened, we could safely take to the road again.

Orel has 80,000 inhabitants, and Turgenev, the writer, claimed it as his birthplace, but after I had looked the town over, I could understand why he had turned Nihilist. The whole place was in a state of senile decay. Garbage littered the main streets, house front gaped dismally, exposing rotten boards and logs where the plaster had given way, and over it all hung the odor of sour cabbage rotting and vermin breeding. There was not a sign of Socialist construction anywhere, all the streets had huge rifts in the road where the rains had washed the cobbles up, and we had to pick our way through the town very gingerly.

We were all very hungry, so I tried the workers’ co-operatives to see if there was anything to eat. There was only black bread sold on ration tickets in one and in the other there was the same cereal coffee I saw up north and few bottles of pickled horseradish yawned dismally on the empty shelves. I saw three restaurants and one cafe, but they each had a large sign on the door, “zagkrit,” closed, so we did not venture to look further.

EGGS 25 CENTS EACH

On the outskirts of the town we came on a huge open-air market. Peasant women were sitting at long wooden tables with bundles of ripe tomatoes and velvety cucumbers spread in front to them. I bought some tomatoes, five dwarfed mushrooms at ten copecks each, and a big bellied onion for thirty copecks and with this we raced off into the woods to cook and eat our meal.

I saw no meat or poultry on sale, nor butter, nor bread, and the one woman selling eggs asked fifty copecks (25 cents) apiece for them. But we had our own store of food with us, and only wanted a few fresh vegetables, so we did not grumble at Stalin’s colhoze markets.

We always had to rein in our steed and pick our way carefully on approaching a town. For some incomprehensible reason Soviet builders always stop short in their good work twenty or thirty miles from a town. A road would run along smoothly for a good long stretch then leave off in a mud-filled ditch.

Sometimes it would give out and disappear entirely leaving you with a sinking heart on one of those wicker-woven bridges that only a government that has 161,000 lives to risk would leave in bad repair. I can still see three bridges, held together by strands of rope and cow dung. They did not look enduring to “Becky,” it always took a lot of entreaty to get her over.

We were just crossing one of these Chinese bridges over the river that should have been called the Don, but is now called by some other name, and I was thinking what a far fall it would be and speculating on the chances of coming up again, when a khaki-clad figure shot out on the road ahead of us and held up hand for us to halt.

HELD UP BY POLICE

It was an O-Gay-Oay-Oo officer, with a trim fast-shooting revolver strapped on his right hip. Beside him leaned a motorcycle of a foreign make. Ah, ha, I thought. A break-down. But we have no room for you. Can’t you see that with three in the front, there is no room for an extra person?

I rolled the window down as he came alongside and started to explain all this. But he stood there silent and only looked us over carefully.

“Where are you bound for?” he demanded. “Kharkov,” I told him. “Your documents, please.” I gave him my press card.

He looked this over carefully, then handed it back to me. “Isn’t this a free route?” I demanded. On the Leningrad-Murmansk route the O-Gay-Pay-Oo patrolled he railway, but they had prisoners in those regions. I could not understand why the highway in this region was guarded.

“You have no prisoners in this district,” I insisted. Why must travellers should their documents?”

He eyed me coldly before replying “There are enemies on every highway. But you may go.”

His words sent a shiver of fear coursing down my back. Was he watching us?

But we were racing through Kursk and on to Belgorod. A few miles more and we would be out of this dismal black-earth region. The peasants here were as unyielding as the soil. A few miles yet and would be treading the sunny white plains of the Ukraine, and we could feel the wind growing softer and air lighter in anticipation.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 12 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 3 under the heading “Girl Writer and Friends Have to Form Company To Buy Gas From Soviet”. Also run on page 3 in conjunction with the continuation of the article above is the map published with the first installment in this series. The map has the heading “NO PRIVATE PERSON CAN BUY GASOLINE” and the following caption:

The black line indicates the route followed by Miss Rhea Clyman, special correspondent of The Evening Telegram, on her 5,000 mile motor trip of investigation from Moscow to Tiflis. In her article to-day Miss Clyman tells of reaching Orel and being forced to form herself and her two companions into a “society” in order to purchase 20 gallons of gas.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 12 May 1933, p. 3.

Girl from New Toronto / Begs Bread in Russia / Father Lured by “Job”

Black Bread or Potatoes Diet of Workers in Huge Dump-Like Tractor Plant

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

Day was just breaking, the first street car was dragging her way up the hill outside my window, we had covered the first lap of our 5,000 mile journey from Moscow to Tiflis without a mishap, and now it was time to be off again.

It was difficult to rouse my sleeping companions. I had got used to the wadded cotton mattress, I knew just where the jumps were, and the brittle sheets were soft now, it was hard getting out of bed. The swelling raised by bed bug bites was subsiding now. Two hot baths had done the trick, and this shabby, dark little room with its broken window panes and dripping water tape, seemed so warm and comfortable.

We had been two days in Kharkov, but we were all anxious to get away. The great Ukrainian capital was in the grip of hunger. Beggars swarmed round the streets, the stores were empty, the workers’ bread rations had just been cut from two pounds a day per person to one pound and a quarter. A young Ukrainian girl, Alice Mertzka, had come begging to our hotel for food. She had lived in New Toronto for nine years[,] her father worked for the Massey Harris Company. Three years ago, she and her father came back to Russia to get work at the tractor plant in Kharkov. “Now we are without bread,” she told me.

FLIVVER IS POPULAR

At six, Becky stood sleek and shiny at the hotel door. The mechanics at the Commissar’s garage had taken to her the moment we drove in. For two days she had stood there with all of her innards exposed. The business of state was forgotten, the Five-Year Plan overlooked, all the brisk young men in the government who drove around in those Studebakers and Lincolns kept in readiness for them in the Commissar’s garage night and day wanted to see how Becky was made. I never believed that I would see our flivver whole again, but here she stood, oiled and greased, purring under the mechanics loving hands.

We were off again. The porters were grinning over their tips, the soldiers marching to their morning bath broke into a song, the children scrambled for candies we threw out, and the traffic cops blew their shrill whistles to hold the traffic until we got clear. We were heading to the great tractor plant. I got my two girl companions started before the restaurant opened, but I promised them that at Tractorstroy, a plant that employed 2,500 workers, there would be a good restaurant and we would get a hot breakfast.

DREARY CITY

How dreary this great city seemed in the early morning light. The long queues of women waiting patiently for the bakery doors to open, the human grape vines clustered on the back of the street cars, the policemen in their frayed mud-green uniforms all looked shabby and bleak. Only Becky seemed pleased to be out.

Those piles of bricks with lumps of mortar still clinging to the edges surely cannot be the great tractor plant. The Soviets do not build their new socialist factories to look like this. These look like a series of badly assorted chimneys flung up on a rubbish dump. Yes, the paved road ended here and bit of green shrubs lay out in front of the door. The eight o’clock bell was ringing, the workers were trooping in.

There was the twang of mid-western American voices. Someone had recognized the car. I left the girls to fraternise with their countrymen and I went indoors to make enquiries.

The office staff was punching the clocks. I stood by the timekeepers’ office waiting for the young man to look up from the big hunk of bread he was eating, and give me some attention. I wanted to be shown the tractor plant, I told the young man when the last crumb was safely lodged away.

“I’m a foreign journalist and I’m anxious to see how your new tractor plant works.”

He did not look up at first, but continued to chew reflectively.

NO VISITORS

We don’t show visitors round the factory now. You’re not a delegation are you? No, that’s a pity. If you were a delegation, perhaps it could be arranged. But you would have to see the directors. They don’t come on duty until eleven. If you want to wait or come back, you can.

I then broached the question of breakfast. All the large plants in Russia have factory restaurants, dining rooms for the workers, we longed to look at theirs and also wanted to see if we could get something to eat there.

“We have no restaurant here,” he replied shortly. “You saw me eating that piece of black bread?―that’s my breakfast and lunch too. Where did you get the idea that all factories have restaurants for workers? They tell the tourists that, that’s all right, they’re foreigners. But you’re Russian, you speak Russian, you ought to know that we workers have no food―khleb bolshey nyet (bread nothing more).” [sic] I did not want to start an argument here, so I asked him if there was anywhere where we could get a glass of tea or a cup of coffee. We did not want to go all the [typo in original – “hte”] way back to Kharkov.

“We have a buffet here of the workers, but it is otchen skverny (very bad) and also does not open until noon. There is a good restaurant for the responsible workers, our director all eat there. It is over in the American corpus (colony). If you go there, you’ll get something to eat.”

WHAT USE MONEY?

But I did not want to see what the Americans working in Russia had to eat. I wanted to know how the Russian workers in this huge industrial plant were fed. I had heard in Moscow that the labor turnover here was from 30 to 40 per cent, the five year program called for the production of 140 tractors a day from this plant, and it had never produced more than 101, but the average was 44. The timekeeper here told me that the average wage for a skilled mechanic was 160 rubles a month. “But what can he do with this money when meat sells for 123 rubles a pound on the open market?” he demanded.

“You say you want to know what the Russian worker eats, I’ll tell you. […] the little man looked round furtively then leaned over the counter, and whispered… ”bread and potatoes. When he doesn’t have potatoes he eats bread, and when he doesn’t have bread he eats potatoes.”

After this I decided that it was not worth waiting three hours for directors. They might not believe that we were a delegation. This tractor plant is the great Soviet showpiece, it had cost over 10,000,000 gold rubles to build and round it grew the scheme for mechanizing agriculture and socializing the land. I could hardly blame the Kremlin for barring visitors―the Russians had begun to call the “tractorstroy” (tractor-build) the “tractorzloy” (the tractor lie).

I went out and told my companions that we would have to forego breakfast. “We’ll get some milk and eggs in the villages en route,” I promised. There is sure to be food somewhere.”

Toronto Evening Telegram, 15 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 3 under the heading “Girl From New Toronto Begs Bread in Russia Father Lured by ‘Job’.” Adjacent to the continuation is the map showing her journey under the heading “Starvation Stalks Through ‘Granary of Russia’,” this time with the following caption:

Miss Rhea Clyman, for four years special correspondent for The Evening Telegram in Russia, to-day describes her visit to Kharkov, the capital of the Ukrainian territory, and the centre of what was once one of the finest farming communities in the world. The fate of these lovable, picturesque people under Communism is described by Miss Clyman. Her visit to a nearby tractor plant also is enlightening.

Also on p. 1 of the same issue is an article with headline “Family Deprived of Relief / Starving Woman Collapses. Weekly $1.25 Voucher Sole Aid of 7 Persons When Township Applies Residency Rule” describing how a 47 year-old woman named Mrs. Thomas Holland was removed from her home and take to St. Joseph’s Hospital when she collapsed from hunger after being cut off from steady relief by a ruling of York Township Council, and thereby reduced to a meager diet of “a few potatoes, carrots and other vegetables for over a week.” [I am missing the second paragraph of the article, which begins with the information that she was living with her son, his wife and their child.]

Toronto Evening Telegram, 15 May 1933, p. 3.

Children Lived on Grass / Only Food in Farm Area / Grain Taken From Them

Mile After Mile of Deserted Villages in Ukrain[e] Farm Area Tells Story of Soviet Invasion

By Rhea G. Clyman

For Four Years Special Correspondent in Russia of The Toronto Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express, and Other Newspapers

It was good to be clear of the smoke of Socialist industrialization of Kharkov, and out into the soft, warm scented air of the steppes again. There were several routes to Rostov, next large city on my strips of paper that constituted our only “map,” and capital of the Don Cossack region. One route ran over the steppes to Mariupol, and another down through the valleys. The lower one led through the Donetz Basin, the heart of the Soviet mining world, the higher one went westward to Dnieperstroy. We came to a fork in the roads, and we stopped and debated. We were nearly five hundred miles south of Moscow, but “Becky” had carried us about 1,500 miles over our wandering course.

The southern route won. I had never been through any of the Soviet mining towns, and I wanted to see how the Communists rationalized toil. The route through the Donetz Basin would be warmer, the blue Ozarov sea was gleaming somewhere in the distance. When the debates were closed, I brought out our Soviet compass and started to plot out the course.

Here is where our troubles began. Only wagon roads stretched out in front of us, the old paved military highway ended in Kharkov. I had only one Ukrainian word, “shliakt,” [i.e., shliakh] meaning main road, to guide me, and I felt like Marco Polo setting out to discover new continents.

VILLAGES OF DISPOSSESSED

We curved out southwestwards. The Donetz River wound its way round like a blue snake at the base of the hills, and we would follow its glowing hide straight to the sea. We were riding on top of flat ridge of hills now, pregnant fields of ripening grain stretched out on either side; thick clumps of castor beans, oceans of golden-headed sunflowers with their faces all turned to the sun, fields and fields of wheat slightly charred and burnt, but not a sign of harvester or harvesting anywhere.

The villages were strangely forlorn and deserted. I could not understand at first. The houses were empty, the doors flung wide open, the roofs were caving in. I felt that we were following in the wake of some hungry horde that was sweeping on ahead of us and laying all these homes bare. In one village I thought I heard a dog barking. I wanted to go back and look, but there was something in the stoical abandon of these homes that [blot on original -terrif?]ied the intuition of a stranger. When we had passed ten, fifteen of these villages I began to understand. These were the homes of those thousands of expropriated peasants―the kulaks―I had seen working in the mines and cutting timber in the North. We sped on and on, raising a thick cloud of dust in front and behind, but still those empty houses staring out with unseeing eyes raced on ahead of us.

It was getting towards noon. We had covered 120 miles since leaving Kharkov, and now we were all very hungry. We had just entered a tidy little village, sprucer and more freshly whitewashed than the rest. I saw a group of white kerchiefed peasant women squatting on the ground with baskets of vegetables and fruit, and I got out to buy some. I looked round for milk and eggs, but no one had any on sale, so I went to first one woman and then another to ask where I could buy some.

WANT BREAD, NOT MONEY

At last I found one who could speak a little Russian. I asked her where I could get a quart of milk and ten eggs.

She eyed me curiously for a moment, then demanded” “You want them for money?”

“Of course,” I answered. “I don’t expect to get them for nothing.”

“You don’t understand,” she said. “We don’t sell eggs for money or milk. We want bread. Have you any?”

At first I thought she meant grain, for in Russian and Ukrainian the word is the same. But when I realized that it was plain ordinary bread she wanted, I could hardly believe my ears! In Russia the villages were forlorn, the peasants ragged and dirty, they grumbled about not having enough food, but they did not ask for bread. If they had anything to sell, they were quite content to let it go for money. Here in the Ukraine, where the peasants seemed so clean and everything well-kept, they wanted bread!

The woman explained that in this village no one had any eggs or milk to sell; the cows and chickens had been slaughtered long ago. They were all starving in the spring. If I drove back with her two miles, into her own village, she would try and find me some. Would four be enough? Then she could manage. She got in beside me, and all the other peasant women left their baskets to call out words of encouragement. This was her first ride in an automobile, she told me, and this the first automobile that had ever entered their village.

TELL THE KREMLIN

When we arrived at the next village, men, women, children and shaggy coats all came crowding out of the narrow doorways. The peasant woman would not step out of the car until every living soul in the village had assembled. Then she started waving her hands, talking and explaining, until I wondered whether she was describing her experience in the car or urging them to some deed of violence.

They wanted something of me, but I could not make out what it was. At last someone went off for a little crippled lad of fourteen, and when he came hobbling up, the mystery was explained. This was the Village of Isoomka, the lad told me. I was from Moscow, yes; we were a delegation studying conditions in the Ukraine, yes. Well, they wanted me to take a petition back to the Kremlin, from this village and the one I had just been in. “Tell the Kremlin we are starving; we have no bread!”

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

“We are good, hard-working peasants, loyal Soviet citizens, but the village Soviet has taken our land from us. We are in the collective farm, but we do not get any grain. Everything, land, cows and horses, have been taken from us, and we have nothing to eat. Our children were eating grass in the spring….”

TORTURED BODIES

I must have looked unbelieving at this, for a tall, gaunt woman started to take the children’s clothes off. She undressed them one by one, prodded their sagging bellies, pointed to their spindly legs, ran her hand up and down their tortured, mis-shapen, twisted little bodies to make me understand that this was real famine. I shut my eyes, I could not bear to look at all this horror. “Yes,” the woman insisted, and the boy repeated, “they were down on all fours like animals, eating grass. There was nothing else for them.”

“What have you to eat now?” I asked them, still keeping my eyes averted from those tortured bodies. “Are all the villages round here the same? Who gets the grain?”

“It is autumn now. We have the vegetables from the garden, squash and pumpkins, and a few potatoes―from that we make flour.” One woman raced back into the house and brought out a black, doughy substance. “Vot nasha khleb (here is our bread),” the boy translated. “Made of dried pumpkins and potatoes. When this is gone we’ll have nothing else. The grain the village Soviet takes away. Our vegetables [that] we grow in the garden will not last the winter. What shall we do in the spring?”

I left this village with the determination that their petition should not only be heard in the Kremlin, but by the rest of the world also. Stalin was building Socialism in one country, and peasant children are eating grass outside the doors of his Socialist cities. After this we understood why the village children always sprang up with stones to hurl at us as we passed. It was their revenge at something that could move faster than those spindly legs could carry them.

Toronto Telegram, 16 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 36 under the heading, “Children Lived on Grass / Only Food in Farm Area”.

_______________________________________

Wife of Communist Boss / Brags to Starved Women / About Her Well-Fed Lot

“Strange,” Russian States to Canadian Girl, “Your Workers Eat Meat and White Bread”

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

“How is it in your country with food products? Can you get white bread?”

The voice came trailing out of the dark, low and husky. It was the woman in the end bed, a worker from the salt mines. I had watched her peeling off layer after layer of clothing until she seemed to melt before my eyes, and when she finally got into bed in a cotton shift that reached to her knees and a long pair of man’s underdrawers beneath, there was nothing but a pair of watchful eyes on the bed! And she wasn’t in the Arctic. She was in a sanatorium six hundred miles south of Moscow.

This was a workers’ sanatorium. Thousands of workers from the key mining industries in the Donetz basin were sent here for vacations and cures every month. When we could find no hotel in Slavinsk to stay for the night, we drove out into a thick pine forest and discovered this sanatorium hidden behind a network of barbed wire.

When we first came in this room had been empty. The nine bare little iron bedsteads had stood stark and naked. But as the evening wore on all the beds were occupied, and later when I got up during the night I discovered several more patients asleep on the floor outside.

“This room,” the nurse explained, “is for latecomers, the patients who arrive on the trains after four o’clock. We only work until four here. In the morning their papers and certificates are examined and they are allotted places in the regular dormitories.

NO SOAP OR DISINFECTANT

I could not sleep. The thin mattress only half concealed the flat boards in place of springs on the bed. The others also complained that they could not fit their shoulder-blades into the grooves already worn. All the windows were closed and the door bolted. The nurse explained that there were so many robberies in this district. The men’s dormitories had been raided last week and quantities of sheets, bedding and clothing were stolen. They had robberies here almost every few weeks. That is why they had soldiers with guns posted inside the sanatorium grounds.

We had nothing but a thin cotton sheet over us. The nurse thought that it might be dangerous to sleep under blankets that were never properly disinfected or washed.

“For us Russians it doesn’t matter,” she told me. “You can’t kill us with anything, but you’re a foreigner and you must be careful. We have all sorts of sickness here and we have no soap or disinfectants.”

All the women were eager to talk. They were all new arrivals, some had been here before, and there were many questions about food and prices that they wanted to discuss. But they were a little in awe of the three foreigners in their midst, and it was only when the worker from the salt mines asked me if the workers in Canada ate white bread and meat that tongues were loosened.

“Of course, they’ve plenty of food in their country,” a Polish woman in the far corner answered for me. She had told me that her husband was a high Communist official. “What a silly question to ask.”

NO MEAT IN 7 MONTHS

“I don’t see why it is silly,” the first woman insisted. “They tell us here that there’s unemployment in America and everywhere. Our papers say that the workers are starving in the capitalist countries, but we have no white bread and they do.”

Here the soda worker in the bed next to mine sat up.

“What I want to know is if the food here is good. Does anyone know whether we get meat here? I haven’t tasted a morsel of meat for seven months, there’s none in our co-operatives and I can’t buy any on the open market with my 90 rubles a month.

“To me food is of no importance,” the Polish woman asserted. “I’ve come here for a cure, my liver is out of order and I need the mud baths here. Food does not concern me.” This was obviously said to impress me.

“How can you get a cure without food?” another woman barked out. “That’s what’s wrong with all of us, not enough to eat. How can you work in the coal mines on potatoes and black bread; that’s all I have to eat at home.” There was a pause, then, “Where do you work that food is no concern to you? Do you get Red Army rations? I know they’re good. I’ve got a married son in the army now.”

“I’m not a worker,” the Polish woman answered languidly, as if annoyed that the conversation should take such a turn. “I’m a domashni khaziika (housewife). I work hard, just as hard as you women in the mines, but I’m not classed as a worker.”

HAIR-PULLING THREATENS

“You are not a worker,” the woman from the soda mine snarled. “Then how did you get into this sanatorium? They only give pootovkas (admission tickets) to workers, members of the trade unions, how did you get your pootovka?”

All the women were fighting mad now. To hear that one of them should calmly assert that she was not a worker. It aroused all their class hatred. I lay back quietly chuckling to myself. The doctrine of the class struggle was taking a new turn, the workers were against the Communists now.

“My husband is the party secretary at Artomvsk,” the Polish woman sat up and explained. She was still addressing all her remarks to me. “The director of the sanatorium is a member of the party, my husband knows him well. When the doctor told me that I ought to go away for a rest my husband long-distanced the director here. I arrived too late to see the director himself, that’s how I came to be put in here.”

There was another outburst of class hatred, but in a lower tone. None of these women wanted to quarrel with the wife of a Communist party secretary, but they had to vent their wrath on someone. For a moment it looked as if it would come to a hair-pulling, because recriminations were endless, and it was five against one. Then a diversion was created. I explained what the Canadian worker had to eat.

“STRANGE, STRANGE.”

“Strana, strana,” (strange, strange), the woman in the bed next to mine whispered. “Your workers eat meat and white bread. We Russian workers live on potatoes and black bread…”

“Yes, it is very strange,” another woman added. “I earn 140 rubles a month, my husband the same, but we can’t feed or clothe our four children. For me it doesn’t matter, a piece of black bread and herring is enough, but growing children need good food. Mine don’t know the taste of butter. I’ve been saving all these months to buy them shoes for the winter but there’s none in the Co-operatives. Strange,” she mused on, “and I suppose that your unemployed eat white bread and meat too?”

I had no chance to answer this. The Polish woman exclaimed pettishly that she was tired of all of this talk about food. She wanted to sleep. “Vot kakya barrinya” (Here’s a lady for you) the woman in the bed next to mine murmured. “She’s not interested in food.” After this there was silence. The glowing moon shifted slightly, and the uncurtained windows lost their silvery sheen. Then I also slept.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 17 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 3 under the heading “Wife of Communist Boss Brags to Starved Women About Her Well-fed Lot”.

_______________________________________

VILLAGE CHIEF STALKS IN / CURTLY ORDERS HOUSEWIFE / ‘GIVE GUESTS YOUR ROOM’

Family of Once “Rich” Peasant Still Persecuted; Coal at Hand, Russians Burn Straw

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

The scene was changing rapidly. The flat open steppes were falling away, and Becky, our flivver, was cantering over jagged, uneven rocks now.

We had not travelled more than ninety miles all day. The roads were treacherously winding; there were no landmarks; all the villages look the same, now that the churches are gone. We got hopelessly lost for a while, but I could see we were on the right road again. A few miles further and we would be groping round in Russia’s mining world.

The air was beginning to thicken with coal dust and soda, and I could taste phosphor and metal by pointing the tip of my tongue into the wind. The sky still had a lovely warm glow. We could have gone another hour, but I wanted to leave the Donetz Basin for the morrow. The village we were entering looked so fresh and attractive that we all decided to spend the night here.

The houses were all freshly white-washed, and the lawns smooth and green. All the roofs were thatched with glistening hay, and the eaves were cut so low that the little houses resembled bobbed-haired children standing out there in neat rows. At first I thought we had slipped into some little hamlet of some other European country. I had never seen such well-clipped hedges or such tall, graceful chestnut trees in Russia before. “This can’t be Russia,” I insisted. “We’re in Germany or in the Tyrol.” Then I noticed a church with belfry and cross gone, and I knew that we were still in Russia.

GERMAN “COMMUNE”

We pulled up outside the biggest building, which, I decided, must be the village Soviet. It was built of red brick and shaped like a church, but I saw men and horses stamping around inside. We tooted our horn and a big burly man came out. I told him what we wanted, and he shouted through the open doorway and two more men came up. The men withdrew to hold a private conference, and then I noticed that they were not speaking Russian nor Ukrainian; the words were not Slavonic, they sounded German.

I called them back and talked to them in German, and they were very pleased. I told them who I was and what we were doing, and after that there was no doubt about their finding a place for us for the night.

This was a German agricultural commune, said the man I first spoke to, and he was the manager. The commune comprised seven villages, all German. There are many German colonies in the Ukraine, but theirs is the largest.

“The church is now the office and the commune centre,” he explained. “Seven miles back is our village Soviet. If you drive back there, we’ll find you a room for the night.”

“It isn’t really a commune,” he told me when we were driving back. “We only call it that. It’s a large collective farm. The people of the seven villages have pooled their land, cattle and machines, and then the profit is shared. No one gets any pay for his work; each member of the commune gets a share of the grain at harvest time.”

HOSPITALITY BY COMMAND

“There was a short meeting at the village Soviet to decide where we were to be lodged. All the officials and the president were in their early twenties, and the party boss was a youth of eighteen. They argued and discussed… “It is important to make a good impression; they are foreigners, and cannot be put just anywhere. There is so much anti-Soviet element in this village…”

Yes, they had found a room. Henrich had one. We went across to Henrich’s house, with all the village trooping after us. Albert, the twenty-three-year-old president of the village Soviet, flung the door open and we all walked in. He told Henrich’s wife, a sweet-faced girl of twenty-two, to sweep the floor and bring fresh hay in, because he had three guests for her room for the night. I did not like this peremptory tone, nor his shoving us into a home without asking the owner’s permission first, but it was too late to draw back.

Henrich was classed as a “rich peasant,” and therefore very much looked down upon by the village Soviet officials. His father had once owned forty acres of land, five horses and ten milking cows. But the commune had taken all this long ago, but still Henrich and his family were persecuted. The house was a simple two-storey building; there were two rooms on the ground floor and two in the attic. Henrich, his wife and five children lived in one of the ground floor rooms―the other was requisitioned for me―and his mother, a crippled sister and three brothers lived in the attic rooms overhead.

“The kitchen,” Henrich’s wife explained, “is out-of-doors at the bottom of the garden. In these regions we don’t cook indoors, the straw smokes so and makes everything black.”

“But why should you use straw for cooking when you’re right in the heart of the coal mining region?”

“WE’LL BREAK PEASANTS.”

She looked at me as if were serious, and then answered: “We don’t burn coal here; they don’t sell us any. Before the war it was different; we have coal ovens in the house; my father-in-law built them. But now we can’t get any coal; it all goes for the industries. We burn straw or peat.”

When the lamps were lit and straw neatly banked in the corner of the stone floor for our bed, all the village Soviet assembled to hear the news from Moscow and abroad.

“Bread, sugar and tea, we have all these things. For those who work there is plenty to eat,” Albert, the president, talked on and on. “We’ve only got one tractor now, but we’re getting two more next year; we’ve been promised two threshers and a combine. That’s better than food or new clothes.”

All these youths were Communists and village activists, and they were all passionate defenders of the socialization of agriculture. Stalin’s policy was their own. The only man over thirty present was Fredrich, the colhoze manager, and he nodded assent to everything.

“We’re building socialism; we can’t stop to count the cost,” one of the youths insisted when I pointed out that the regions one hundred per cent collectivized reported the worst crops this year. “We’ll break the peasants. Those who do not go our way will be plucked out and flung away . . . five, ten years from now all these difficulties will disappear. The youth who spoke thus had nothing of the soil about him. He was a Jewish lad from Odessa, and now the organizing secretary here.

We were up at dawn the next morning; we wanted to make an early start, but it was hours before we could get away. The school bell rang and rang; the teachers come over to urge the children to go in to school, but all the village was assembled round us to watch us pack, and the children begged to stay for the start. We got the whole village to pose for our cameras, and I autographed 52 children’s note-books. Then there was a rousing lusty cheer, more ringing of the school bell and a short “Auf weder zehen.” [sic]

Toronto Evening Telegram. 17 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 3 under the heading: “Village Chief Stalks In Curtly Orders Housewife Give Guests Your Room”. Adjacent to the continuation of the article is the map used for the series under the heading “German Commune Picturesque Patch of Russia,” with the following caption:

On the fringes of the Donetz Basine the great Russian mining district just north of the Black Sea, Miss Clyman came upon an idyllic scene ― a neat, apparently prosperous hamlet like something lifted from Germany or the Tyrol. The German commune, as it proved to be, is described in to-day’s article by Miss Clyman, who was for four years The Telegram’s special correspondent in Russia.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 17 May 1933, p. 3.

EXPLOSION EVERY WEEK / ACCIDENT EVERY HOUR / IN RUSSIAN COAL MINE

Twisted Men and Bloodless Children Live in Sorry Tarred Huts Near Pit Heads

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

Those who believe that the Soviets are great planners, and who think that the Communists are honest whenever they say that the welfare and interests of the workers are the first consideration in socialized industries, should go for a trip through the Donetz Basin in the Ukraine.

I do not mean the large old towns like Slavinsk, Bakhmut or Nikitovka, they are all covered with the grime of eight or ten generations, but those new proletarian cities like Gorlovo, Stalino, and all those other workers’ settlements that have grown up since the five-year plan began. For sordid ugliness they are hard to beat.

Mining is a key industry in the Soviet Union now, but despite all the efforts of the Kremlin, the output of coal and iron ore has never been more than 40 per cent of the amount called for by the five-year plan. After inspecting the mines and talking to the men and women who work in them I understood why the engineers and mechanics who are sent there to work from Moscow feel that they are going out to exile and prison.

We arrived in Gorlova [sic] in time to witness the weekly explosion at the shafts. No one was killed this time. I saw two men and a woman brought up on a stretcher. The manager told me that they had a bigger and better explosion last week. Four of the richest coal veins are worked here: the mines are equipped with the best and most up-to-date machinery, but the workers and engineers are all over-worked and under-nourished so fatalities occur. The manager would not admit that the miners were openly sabotaging.

SCARCELY HUMAN

“Ninety per cent of the workers here are unskilled,” an engineer here explained. “We have a labor turnover of 40 and 50 per cent every month. Of course these people are careless with machines, and we have accidents here every hour.

In Stalino, the capital of the Donbass [sic] mining district, we saw a block of new workingman’s flats. After the miles and miles of dark, narrow little shacks, some of them only bits of beaverboard held together by sheets of tar paper, sticking up like ugly, putrid-smelling fungi round the mouths of the mine pits, this huge grey-faced building was a welcome sight. It was just two o’clock; the miners were returning for their noon-day meal, and the moment we stopped we were immediately surrounded.

I looked at these people. They hardly seemed human. Young men and boyish faces were bent and twisted like gnarled old tree trunks. The women were black and covered with soot; the children looked as if every drop of blood had long been squeezed from their veins. They packed solidly round us, and we had to roll the windows up to keep them from fingering and touching our belongings.

I asked if any of them lived in these new apartments, because I wanted to see the rooms. The men shifted uneasily from foot to foot, and some of the women broke out into a toothless grin.

“Tom jivyot loodi, no mwi nyet” (people live there, but not we), a raw-boned peasant woman spoke up. “Mwi chorni robotchi (we are unskilled labor), we live near the mines. These apartments are for the mechaniki (mechanics and skilled workers). But go up, they’ll show you what they’re like.

MODERN INCONVENIENCES

I mounted first one flight of stairs and then another. The doors were all locked and bolted, and no one answered my knock. Then, on the fourth floor, I found a door that was open, a woman was moving within. Yes, all the apartments were the same. She showed me her three small rooms. They were fresh and clean, but the plaster was crumbling from the walls, the wood was warped, and the doors and windows would not close. In the kitchen there was a coal range, but on it hissed a primus and over near the sink was a wooden tub of water.

No, the water had not been turned on yet; the pipes were all there, but not connected yet. “I’ve been here for a year and a half, and every month they promise us water, but they haven’t given it to us yet. The lavatories. . . .” a wave at the wide open spaces at the back. “The kitchen stove? No coal.” She did not work in the mines. She was expecting a baby any day now. Did she draw money from the health insurance as an expectant mother? “No, I’m a housewife. I’ve four small children already. I couldn’t go to work and have them. Only women in industry get four months off with pay when they are bearing children.”

Her four children were under ten, she told me, but they had not received a drop of milk for six months. She got some milk for them from the peasant women for bread, but the workers’ co-operatives did not issue any. Each child received a pound and a quarter of macaroni and rice a month, and a pound of bread a day, their ration of margarine (200 grams a month), and sugar (2 pounds a month), was behind, but she expected that they’d be giving it out soon. “Meat, butter or eggs,” she smiled when I mentioned these. “Nyet, nyet, dyeing nye khvatiet (there isn’t enough money for these).

As we were threading our way out through the town, and out toward the road that led to Taganrog, a port town on the Sea of Ozerov, 100 miles to the south, we came on another miners’ settlement. The houses were square little boxes of clay and beaverboard, the roofs covered with strips of tar. Each little street had a large open kitchen, a wood or coal range roofed in with strips of tar and paper. This is where the mine women in the Donbass cook the family meals.

LONGS FOR “CULTURE”

Kurkina, a woman of thirty-eight but looking nearer fifty told me that she earned 50 rubles a month working in the pits. She was stirring a large pot of barley, and the sparks and soot from the open stove kept leaping up from the fire, were caught and drowned in the sticky mess, but Kurkina stirred on unconsciously at the additional ingredients in her food.

“Yes, we get sugar, two pounds a month. The children used to get a quarter of a pound of margarine a month as fat, but not now; we get two quarts of sunflower seed oil for the family instead.”

Masha, a big, broad-shouldered woman, came over to look into her pot, and Nura and Shura, and all the children, because they saw our cameras pointing that way.

“Ah, it must be wonderful to have culture,” said Masha. “We poor Russians, what do we know of the world? We stand like animals with our noses in the ground all day.”

They asked us to come in and share their meal of barley and boiled potatoes, but we had smelt the sea somewhere off in the distance. We had two days of this smoke-laden air of the Donetz. A few miles off, beyond the horizon, lay the Ozerov Sea and Taganrog. We were anxious to be out of this mining region, bare of shrubs and trees, and where every corner was infested with human ants, and every hill was shooting lava and polluting the air. The towns were worse than the villages, young men and half-grown boys lounging outside the corner liquor stores, spitting husks of sunflower seeds across the road. The did not look human; they seemed like withered, musty, tree stumps flung out of the bowels of the earth to dry and rot in the sun.

BEATS THE RITZ

We did not get to Taganrog until after two, and another two hours went before we could the O-Gay-Pay-Oo to help us get gasoline; then we fled the town and pushed off to a narrow strip of beach. We had our first bathe and wash in fourteen days, and while the girls were out swimming and doing the family wash, I experimented with the cooking. I prepared two large pots of rice and tomatoes, sprinkled it with the cheese I scooped out with a knife, then digging in the food box, I discovered two wrinkled red peppers, and I put them in also. When the girls came back all tired and hungry from their baths, they swore that neither in the Hotel Algonquin, nor in the Ritz, had they ever tasted anything so good!

We were nearing Rostov, the Don Cossack region; we had left the hungry Ukraine behind; we could afford to take liberties with our food box, so I brought out a tin of tuna fish and a bar of chocolate to round off the meal.

At nightfall we were in Rostov, seven hundred miles south of Moscow, but we head driven nearly 2,500 miles to reach it. Half our journey, unknown to me then, had been completed.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 19 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 15 under the heading “Explosion Every Week Accident Every Hour in Russian Coal Mine.” The map depicting Clyman’s route was also reproduced at the bottom of the continuation of the article with the heading “Misery of Soviet Mines Shows Workers’ ‘Uplift’,” and with the following caption:

A scarcely human-seeming population, under-nourished, over-worked and over-crowded was the demonstration of the Communists’ love for the worker which Miss Rhea Clyman found on the way through the Donetz Basin, Russia’s great coal mining district. Miss Clyman, who was The Telegram’s special correspondent in Russia for four years, tells of the conditions she saw as her tour took her through the towns of Gorlova, Stalino and Taganrog.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 19 May 1933, p, 15.

Women Harvesters Toil / Under Threat of Rifles / On Soviet ‘Collective’

Soldiers Surround Dispossessed Cossacks Soon to Be Exiled to Frozen North

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

Soldiers in the streets of Rostov, soldiers on parade, soldiers singing on their way to the bath-house, and soldiers guarding fields and warehouses, every inch of the Cossack region now has the imprint of a Red army heel.

“Why are there so many troops about?” I asked the men who were pulling the little raft on which our flivver “Becky” and we were ferrying across the River Don. “I’ve never seen so many soldiers in the north.”

The two men stood harnessed with ropes and chains like galley slaves of old. This was Rostov, the great centre of Socialist building and construction, but the bridge over the Don had not yet been built yet, and we crossed the waves as Ghenghis Khan did.

“The soldiers,” the old man answered, after he had finished pulling and tugging, and spitting on his hands, and pulling harder at his chains, “that’s the army of occupation. Go into the villages. The harvest is on now. You’ll see what the soldiers are doing.”

STUPENDOUS EFFORT

It was good to be out on the road again. The fields were alive with harvesters, the hum of threshers vibrated in the air. With one stupendous effort the whole nation had been mobilized to bring the grain in. Men and women strode through the golden fields like sun-worshippers; men swinging hooked loops of steel right and left, and the women following behind to gather the sheaves, and all walking out together with glowing burdens into the face of the sun. But they had not come out soon enough, for many of the sheaves that fell under the hack of the knife had already lost their fruit to the wind and rain.

Beyond Batalsk [possibly Bataisk?], the town where Europe meets Asia and the time changes, we came on the largest group of harvesters we had seen yet working on the fields together. Five threshers were all going at the same time, and over two hundred men and women stood enveloped in a shroud of dust, raking and cleaning frantically to keep pace with the greed of the machines. I went over to speak to a group of women crouching in the shade. They were nursing their babies.

“How much do you get for your work here?” I asked a woman with a pock-marked face. She had on a white, clean apron.

“Twenty-five copecks (14 cents) a day.”

14 CENTS A DAY

“How many hours a day do you work, and is that all you get?”

“We work as long as the sun is up and it’s light. We don’t get paid by the hour; we work as long as there’s daylight.”

“But surely you get food besides?” I insisted. “You can’t live on 27 copecks a day; you can’t buy anything but a newspaper with that.”

“We colhozniki (collective farm members) have to live on anything now, and older woman answered. “The 27 copecks is not pay, its avance (an advance). It will come out of our share of the flour later on. Last year we got seven poods of grain (48 lbs. one pood) for our year’s work; the crop this year is worse, and we’ll get less. We don’t get the harvest we used to get when the fields were our own. Who cares what grows now?”

The manager, a slight little man of about 35, came up to say that the rest time was over. The nurslings were left in the shade, some covered with bits of straw sacking, others with the think jacket of the mothers. A group of older children were there to shoo the flies off the sleeping babes, but they were now too engrossed in our cameras, so the poor neglected babes whimpered and moaned as the flies bit and tore.

CAMP IN FIELDS

“Nursing mothers get fifteen minutes off in the morning and fifteen in the afternoon to feed their babies,” the manager explained. “Everyone gets two hours for dinner,” and he took me off to where the dinner was being prepared―large, black caldrons of potatoes in the jackets hung over an open fire, and another of soup, with greasy hunks of mutton floating on the top, stood ready cooked.

“All the workers get a bowl of soup and a dish of potatoes for dinner, and when they don’t go home at night, we give them bread and tea. Sometimes, when the work is to far from the villages, we camp right here in the fields.”

“But what about the babies?” I demanded. “Do they stay out in the fields all night?”

“Oh, yes… We have no nurseries in our district, the mothers have no other place to leave them.”

We stayed with them while the workers were having their dinner. The women drank a few spoonfuls of soup, and then passed it to the men, and they swallowed a few mouthfuls and passed it back again. If there was any meat left at the bottom, it was taken out and shared morsel by morsel. After this meal was over, the men pulled up wagons full of luscious watermelons. They tossed us two, and the rest they broke over their knees and then handed the melons to the women to divide.

MALCONTENTS SHOT

“What do you think of collectivization?” I asked the man who seemed to be the leader of the clan. I noticed that not all the workers sat together; they formed little groups round a pot with one man and woman at the head. The dishes of potatoes were shared out turn on turn, but whether in patriarchal or matriarchal order I could not tell. “Do you think collective farming is an improvement over the old way?” I asked.

“For us it means ruin,” the old man answered. “But perhaps for our children it will be better. Who knows? On this land we were born and bred, but now the fields are not ours, and the bread we are now cutting will go into other mouths, not our own. But we can’t stop working because of that. There are people here who wouldn’t work. Strangers now live in their houses; the fields don’t stop bearing because the owners are dead.”

“Have there been many arrests and shootings in this region since Kalinin signed the new decree?” I knew that there had been a lot of trouble here; in Moscow there were rumors of a peasant uprising in this region.

“We mind our own business; we don’t know what is going on. If a man or a woman disappears we know they’ve been shot, but no one asks any questions.”

DEPORTED 5,000

The machines were starting their clamor again; the place where the workers had been sitting was now swimming with watermelon rind and slippery seeds. It was time for us to be off again. We began to notice that the fields here were all patroled [sic] at night; every few yards there were little rickety wooden watch towers, men with drawn rifles stood there night and day.

“This was the Don Cossack region,” I explained to the girls. “This ground breeds fighting men; there’s no stoical submission here. All those workers we saw in the fields to-day will go home with a bag of seeds under each arm. The new Soviet decree calls for a death penalty on those caught stealing or damaging collective farm property, but these Cossacks will face death rather than submit.”

I was only too right. Two months after I left Russia, news was received that 5,000 Cossack families, entire villages, were arrested and deported from this region. I did not know then that those golden fields would soon be soaked in blood, nor that the old wooden rifles I saw hidden among the sheaves of corn and wheat meant war. I can still see these happy, sun-loving people sinking their white teeth into the luscious red watermelons, those young babes whimpering in the shade when flies nipped and tore. How many of them are in the frozen north now? How many will survive the uprooting from the soil and the bleak Arctic winters?

Toronto Evening Telegram, 22 May 19322, p. 1, continued on p. 14 under the heading “Women Harvesters Toil Under Threat of Rifles On Soviet ‘Collective”. The map used for this series is reproduced above the continuation under the heading “Fields Run With Blood of Cossack Farmers” and with the following caption:

Two months before the Soviet exiled 5,000 Don Cossack families to the deadly rigors of North Russia, Rhea Clyman had a glimpse of these sturdy, independent farmers in their home region, and saw their rebellious acceptance of the slavery that compelled them to toil from sunrise to sunset, in fields that had once been their own, to gather a “collective” harvest. To-days article on the Don Cossacks is the eleventh of a series by Miss Clyman, who was for four years The Telegram’s special correspondent in Russia.

Toronto Evening Telegram, 22 May 19322, p. 14.

Peasants Live in Ground / Machines Rust in Fields / On Russian State Farm

“Everyone is Master and Everything Goes to the Devil,” is Native View of “Liberty”

By RHEA G. CLYMAN

For Four Years Special Correspondent to Russia of The Evening Telegram,

London Daily Express and Other Newspapers

Thump, thump, thump. I sat up with a start. Our beds were swaying with the sound: there was only a faint streak of daylight coming through the open window and from where came those thumps of marching feet?

This was Verblud, the famous grain trust colhoze. Russia and the rest of the world had their eye on this huge experiment in state agriculture. This was the Soviet Government’s grain factory, the first move in the plan for socializing agriculture. Had the Soviet experiment failed here too?

“Quick, Alva, the cameras,” I shouted to my companion. I suddenly espied a column of soldiers coming down the road. The light was still too dim to make out their regiment, but when they came nearer and turned the bend of the road, a flick of the sun brushed across their khaki forms and the crimson colour of their neck-bands and should glowed like a flame. It was the O-Gay-Pay-Oo, marching 600 strong, and click went our cameras.

I was getting up. We had arrived at Verblud the previous night without warning. There is a hotel here specially for foreign tourists, but they had made a fuss about taking us in. The two State farms, Verblud and Gigant, are the largest in the Soviet Union, and up to last summer special excursion trains were run here from Moscow, the Communists were so eager to show what mechanized farming would do for Soviet agriculture. But recently the region was closed to foreign tourists, the State farms were taken off the itinerary of the tours organized by the Soviet travel bureau, and our press cables about the arrests and shooting of State farm managers because the crops had failed were heavily censored.

HARD-FACED TENEMENTS

The clock was just striking six when I came out. The hotel stood in the middle of the residential section, five paved streets ran out like points of a star, the long rows of zigzag tenements looked strange towering up in the midst of vast empty prairie. I had always associated tenements with crowded streets, slums, but here they stood, one block after another, with that ugly, hard-faced newness that hastily flung up buildings always wear in Russia.

The Soviets have 15,000 acres of land here; they could easily have up three or four-family duplex bungalows that would go with the landscape and surroundings, but instead of this they threw up these huge zig-zag box tenements which except for their newness might be sitting out in East Side New York.

At the turn of the road, I came on the machine shops and factories. Verblud has its own tractor and repair plants and employs over 1,000 skilled mechanics. One large field was filled with old broken-down machines; tractors, combines and threshers were all bunched together; here a wheel was missing; there a side was gone; tools and spare parts lay forgotten and rusty in the tall grasses. Some of the machines looked quite new; a few were imported and others were Soviet make, but they were all rusty and dismantled.

“HERE LIES OUR WEALTH.”

“Vot nasha bogatsvo (Here lies our wealth),” someone murmured behind me. I turned around with a start. A Russian workman in a pair of frayed cotton trousers and white shirt stood at my elbow. I had not heard him come up because he was barefooted and carried his shoes under his arm.

“What are all these machines doing here?” I asked him.

“That’s Stalin’s method of making us machine-minded. Here’s all our wealth; machines thrown out on the scrap heap after a few months’ use. But why should we treat a machine better than the government treats us?”

I had no answer to this question so he hurried off. I crossed an open field, the sun was warmer here, over beyond the barns and grain elevators, the fields were dotted with black mounds. Thousands of bare-footed peasants were now swarming out of them. When I came closer I discovered that these lumps of earth were dugouts. There were rows and rows of them, built out of bits of wood and plastered over with cow dung and straw, the doorways were so low that the people coming out of them were bent in double to crawl through. I wanted to enter one of these hovels but I had to give up, the stench of human body and cow dung was took great.

A woman was just getting up from her bed on the moist ground. She had been sleeping with all her clothes on. Her toilet was quickly made; she took a sip of water from the pail outside, spat it out again into her hands and then rinsed her face with it; then she picked up her shawl, used as a mattress and cover, wrapped herself in it and was ready dressed for work.

BURROWS FOR BARRACKS.

“Who lives in these dugouts?” I asked her when she got finished with her ablutions.

“These are the barraki (barracks) for the seasonal workers, the peasants. Over there,” with a flick in the direction of the zig-zag block of tenements I had just come from, “live the workers and mechanics; they work in the offices here and the machine shops. We peasants that work in the fields live here in these barracks.”

Lusha was full of hard feeling at the class distinctions shown to the workers on Verblud. The men in the machine shops lived in beautiful four-roomed flats; they got good pay and meat rations twice a week. She was also a skilled worker; she knew everything there was to know about the land. She had once owned an acre and quarter of her own, but she was a peasant so she had to work for a ruble ninety a day and feed in the third category restaurant where there was nothing but salted fish and boiled potatoes and corn mash to eat.

“I’ve been here nine months,” she told me. “I wouldn’t have stuck it as long as this, but I’m a widow with four children to feed. There’s no bread in the Ukraine. I came here to work because they give us a pound of black bread a day; this I can send home to the children.”

The Soviet Government gives no widow’s allowance or pension as we do in Canada. The care of orphans devolves on the nearest relative. In my flat in Moscow an old woman of 60 was looking after her niece, left an orphan at four.

We were walking across the fields and Lusha was telling me about her life in Odessa, and how difficult the peasant’s lot was now, when she suddenly stopped still, looked around stealthily, the placed her mouth close to my ear and whispered: “Have you got a Master in your country?” I did not understand, so she repeated it again. “Have you got a Master, a King or a Tzar, a real master?”

FREEDOM―FOR WHAT?

I understood now. “Yes, we have a king in our country.”

She looked quickly round and grabbed my hand. “That’s good. A country must have a master. In Russia now everyone is master, and everything goes to the devil.”

I looked at her in amazement. I could hardly believe my ears. “Do you want the Tzar back,” I asked her. [“]You have freedom now, the peasants didn’t have that in the old days.”

“Svabodi (freedom),” she snorted. “For what? I could earn my ruble ninety in the old days, and it bought something then. And who’s free? The workers perhaps. There are 300 leshentzi (peasants without rights of citizens) working on this sovkhoze now, forced labor, are they free? The peasants have no freedom now; we had it when the land was ours, but collectivization has done away with that.”

It was time to go back and see what the others were doing. Lusha had shown me the barns where she worked, the half empty bins, the little empty pellets that would be ground up as flour for the workers. She told me that the 15,000 acres were being broken up, large scale farming had failed to produce grain. Verblud was being worked in 12 sections now. I had heard rumors of this in Moscow, and now it was confirmed; the factory plan for producing grain had broken down.

HOTEL BESIEGED

When I got back, I found the hotel besieged. Men, women and children, armed with pots, pans and dishes, were crowded round the entrance and banging on the door with their fists. I thought it was a bread riot or a hunger march; then someone explained that this hotel served meals to the “responsible workers,” since the foreign tourist season had ended. This was the first category dining room, and only “responsible workers” could get their food here, but today the kitchen was late.

I sympathized with these men and women because I was hungry, too, but I saw that there was nothing to be gained by making a noise. I decided to go across the street and look at some of the workers’ flats in the tenements opposite. I tried first one door and then another, but no one was in. They were all lined up outside the hotel kitchen. I tried the next apartment house; it was the same; then I went into a third.

On the second landing I could hear someone moving inside. I knocked and a large moon-faced girl, her hair screwed up in curl papers and a thin cotton kimono stretched to a straining point across her ample form, came to the door. Yes, all the flats were the same; hers was a three-roomed; she only had one room, two other families lived with her, Everyone shared the same kitchen and bathroom.

A string of black papier mache [sic] beads hanging on her wall bracket caught my eye. “Did you make these yourself?” I asked her.

The girl burst out weeping, huge tears rolled down that flat face like water from a tap. “He gave me these. . . . I thought he loved me. . . . He’s gone, let me flat. . . .”

She started to give me all the details, but this huge creature looked so grotesque, I got up and fled. A love affair begun on a string of papier mache beads might be interesting but I had seen the line outside the hotel moving in, and food was more important at this moment.

Toronto Telegram. 23 May 1933, p. 1, continued on p. 31 under the heading “Peasants Live in Ground Machines Rust in Fields On Russian State Farm”.